Recent Russian debate on moving from VAT to sales taxes and its global implications

Vera Kononova, John Whalley

Abstract

We discuss recent policy debate in Russia on moving from the present value added tax to a sales tax structure covering households, government and exports. What is distinctive in this debate is the range and nature of problems identified with the VAT, most of which stem from its multistage credit-invoice mechanism. These include false credit and refund claims, delays and difficulties in obtaining legitimate input credits and refunds reflecting responses of tax authorities to false claims, difficulties for large firms dealing with small firms, and resulting uneven effective tax rates between energy and manufacturing sectors. For the Russian economy being heavily dependent on oil and gas exports and seeking diversification, the VAT effectively places industrial companies at a significant disadvantage, particularly compared to exporters of energy resources. These problems are all intensified by the relatively high statutory rate of 18% in the Russian VAT. We describe and document the debate, discussing in detail what the perceived Russian problems with the VAT are. We suggest that many of the difficulties reflect the multi staging in the credit-invoice mechanism in the VAT, rather than the VAT per se. We discuss the possible use of the subtraction and addition methods in the VAT as an alternative to the sales tax proposed. We also report estimates of possible changes in effective tax rates across sectors if the sales tax were enacted. The final outcome of this debate is not yet known. A special commission of the Presidential Executive Office of the Russian Federation was to report on the matter in 2009, however, due to the economic crisis a decision on VAT/sales tax has been postponed. Despite this, in the near future a change to a sales tax could possibly follow. We suggest that were this to occur this would be a precedent setting move away from the value added tax. With IMF and World Bank conditionality no longer the force that it was for policy change in large economies such as Russia, India, China and Brazil, similar re-examinations could follow elsewhere. Vera Kononova The Institute for Complex Strategic Studies Graduate School of Business Administration Moscow State University kononova@icss.ac.ru John Whalley Department of Economics Social Science Centre University of Western Ontario London, Ontario N6A 5C2 CANADA and NBER jwhalley@uwo.ca2 See also the discussion in Lockwood and Keen (2007)

Introduction

Conventional public finance literature in the time when the value added tax evolved in its present form in most countries (Japan in the late 1940’s, France in the early 1950’s) stressed the formal equivalence between single stage sales taxes and multi stage value added taxes and advocated value added taxes largely on administrative grounds (see Shoup (1974)). The VAT, it was argued was self policing through matching invoices for buyers and sellers in intermediate transactions. Compared to a sales tax, VAT allowed avoiding administrative determination of what was or was not a final sale, and involved significant tax collection at early stages of production where small numbers of larger producers yielded higher compliance compared to later stages such as retailing. The VAT was adopted in France in 1954 as a mechanism to remove cascading in the prior turn over tax through crediting of taxes on inputs, later became the indirect tax harmonization target for the EU in the 1960s, and then driven by World Bank and IMF conditionality later spread to over 120 countries.

Here we discuss recent policy debate in Russia on moving back from the present value added tax to a sales tax structure covering households, government and exports. What is distinctive in this debate is the range and nature of problems identified with the VAT, most of which stem from its multistage credit-invoice mechanism. There include false credit and refund claims delays and difficulties in obtaining legitimate input credits and refunds due to tax authorities reactions to false claims, difficulties for large firms dealing with small firms, and resulting uneven effective tax rates between energy and manufacturing exports. Some of these problems are known from other country experiences, and especially fraudulent claims for export rebates and false invoices for input credits from transient companies. But others are more distinctive. These include tax administration responses through onerous reporting and auditing requirements that effectively drive many legitimate claims to court process, and impose costs and delays on business that in effect cause the credit mechanism in the credit-invoice VAT to function extremely imperfectly. For the Russian economy being largely dependent on oil and gas exports, the VAT also effectively places industrial manufacturing companies at a significant disadvantage compared to exporters of energy resources, especially if their production processes span many intermediate products and supplies. These problems are all intensified by the relatively high statutory rate of 18% in the Russian VAT.

A central theme of the paper is the recognition in Russia that indirect tax design in Russia inevitably takes place in an environment in which administrative problems unique to a multi stage tax arise when corrupt practises are extensive. This central feature is missing from older debate on VAT and sales taxes but is paramount in Russia. The central argument against the VAT is thus that a multi stage tax with crediting and rebating of taxes on exports seemingly inevitably creates administrative problems and provides more opportunities for corruption to flourish than is the case with a single stage sales tax. We also suggest that other administrative mechanisms could be used to administer the VAT, including the subtraction and addition methods. The traditional problems with sales taxes – relying on tax collections from large numbers of small retailers and problems of defining retail sales and administering either a retail sales or wholesale level sales tax – in an economy such as Russia are far from easy to resolve. But the traditional case for the credit-invoice VAT over the sales tax emerges is much more nuanced and in the Russian case may not hold.

In what follows we describe and document the debate, discussing in detail what the perceived Russian problems with the credit invoice VAT are. We also report estimates of possible changes in effective tax rate across sectors if the proposed sales tax was in effect. The final outcome of this debate is not yet known. A special commission of the Presidential Executive Office of the Russian Federation was to report on the matter in 2009. However, due to the economic crisis the question of VAT/sales tax reform has been postponed. Despite this, in the near future a change to a sales tax could possibly follow.

We suggest that were this to occur, this would be a precedent setting move away from the value added tax. With IMF and World Bank conditionality no longer the force that it was for policy change in large economies such as Russia, India, China and Brazil, similar re-examinations could follow elsewhere. Indeed, even in some OECD economies such as Canada the VAT remains an unpopular tax and some of the difficulties discussed in the Russian case (such as export rebates) are also present. While it is premature to talk about a reversal of the VAT fiscal bush fire that has swept the world in the last 50 years, we nonetheless suggest that this Russian debate and its new element of the credit- invoice VAT facilitating corrupt practices may at least be the beginnings of a questioning of the VAT’s supremacy, or even a partial reversal of trend.

The Russian VAT and debate on reform

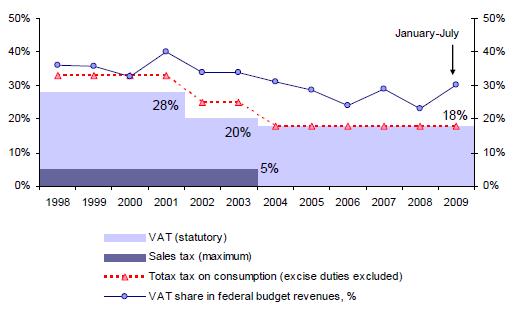

The history of VAT in Russia begins in 1992, when a credit-invoice VAT was introduced in place of the Soviet style turnover tax. In 1992-2001 the basic VAT rate was 28%. In 2002-2004 it was reduced to 20%, and since 2004 the basic rate has remained at 18%. The VAT is a federal tax, and is now one of the major sources of federal budget revenue. The VAT contributed about 23-30% of federal budget revenues over the last five years. The share of VAT in budget revenues has decreased slightly over time (Figure 1), but is in the 30% range. In response to false claims for credits and export tax refunds, increasingly onerous reporting and auditing procedure have evolved.

Since 1992, the VAT been modified by changing the list of taxable business operations, lowering tax rates, changing tax periods and in other ways. The VAT is now considered take one of the most complicated taxes in Russia, in contrast to the simple tax proposed by VAT advocates in the 1940’s outside of Russia. These complications have generated both large compliance costs for business and problems in administration for tax authorities. VAT collections have been relatively low, by international standards. There are estimates for 2004-2007 that only 50-60% of VAT liabilities resulted in collections.

Alongside the VAT, Russia also has experience with retail sales taxes. In 1998 the sales tax was introduced as a regional tax with a maximum rate of 5%. The tax covered all retail transactions in cash or non-cash form, with the exception of basic foods, children’s clothing, housing services and other goods and services considered socially important. The tax rate was set by the regional authorities, and tax revenues were shared between regional and municipal governments. Almost all regions of Russia introduced a 5% sales tax, increasing the total indirect tax burden on consumption to 28% in 1998-2001, and to 25% in 2002-2003 (excise duties excluded. See Figure 1).

Figure 1. VAT and sales tax rates and revenue share of VAT in Russia, 1998‐2008

Source: Tax Legislature of Russia (1998, 2001, 2003, 2004)

In 2004, the sales tax was repealed for a number of reasons. First, cancelling the sales tax was a part of tax simplification policy adopted in the beginning of the 2000s, reducing the number of taxes. Second, the tax was also viewed as difficult to administer on a local and regional level, and sales tax collections were also rather low. These difficulties reflected the traditional problems of sales taxes of collecting revenues from large numbers of small retailers, and issues with the definition of final sales. Since 2004 VAT has been the only tax on consumption in Russia (except excise duties) for a limited number of goods.

But since 2006 due to the problems listed above with VAT, there is an on-going debate on possible further VAT reform. Discussions on VAT reform have been held at various levels and involved government officials, business associations (including the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs) and expert groups. In 2006-2007, the most widely discussed proposal was to decrease the statutory VAT rate to 12-13%. The supporters of this change argued that a decrease in VAT rate would produce a substantial stimulating effect on the manufacturing sector and promote additional investment. The claim was also made that if the VAT rate was no higher than 13%, this would greatly weaken incentives of tax evasion, as the costs for using evasion schemes would be roughly the same as tax payments saved and the VAT collection rate would rise.

The idea of decreasing the VAT rate was strongly opposed by the Ministry of Finance, who argued that such changes would undermine budget stability. However, there was a substantial budget surplus at the time (7.5% GDP in 2005, 7.4% GDP in 2006) and as a result, in 2007 President Putin in his Annual Address to the Federal Assembly proposed that VAT should be reformed and probably decreased to the “lowest possible rate”.

At the same time, an alternative direction for VAT reform – the restoration of the retail sales tax in place of the VAT emerged. This idea, originating with the Presidential Executive Office, was further developed by the Finance Academy under the Government of the Russian Federation. The idea of substituting the VAT with a 10% sales tax was seen by industrial manufacturers as attractive, since they would be little involved with final sales. In 2007 the idea of introducing a 10% retail sales tax instead of the VAT was formally supported by the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs. However, the sales tax alternative was questioned by the Ministry of Finance on the basis that the idea had not been investigated deeply enough.

In 2008, President Medvedev accepted that there were on-going problems with the VAT and encouraged further discussion of reform. The Ministry of Economic Development made preliminary estimates of the possible impacts of decreasing the basic VAT rate from 18% to 12%, and the Presidential Executive Office continued to investigate the possibility of substituting the VAT with a 10% sales tax. To date no final decision has been made. Discussions concerning VAT reform were scheduled for August 2008, but were postponed due to the economic crisis. The “Key directions for tax policy for the Russian Federation for 2010 and the planned period of 2011-2012”, adopted in May 2009 by the Government, did not include any decisions with regard to the VAT or tax rate or sales tax. The details of the sales tax mechanism to be used, such as the exact definition of final sales, the taxation of small business sales, transitional issues with substituting of VAT with sales tax, have not yet been spelled out. There are also no estimates for the impacts of sales tax VAT substitution, including cross-industry effective tax rates, sales tax collection rates, and potential budget revenue impacts.

Discussion of VAT issues raised in the debate

The debate on VAT reform in Russia has focused on issues which have made the VAT complicated both for taxpayer companies and for tax authorities. Most of the issues involve the VAT credit-invoice mechanism, and originate with low tax discipline and corrupt practices existing in Russia and the responses of tax authorities to these. The central issues are exemptions from VAT, including refunds of inputs credits for exporters substantiating input credits for domestic producers, the tax treatment of small business units, and suppliers of some “socially important” goods and services. Taking into account the current structure of the Russian economy by sector, the argument is that these problems with the VAT produce obstacles to economic development in Russia since the effective tax rate on the manufacturing section is very high. The most broadly discussed issues in the debate are listed below (Table 1).

Table 1. List of broadly discussed VAT issues entailing higher costs for business and tax authorities in Russia

|

Business sector ‐ taxpayers

|

Tax authorities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VAT issues for taxpayers

Large private compliance costs. The most widespread argument against current VAT in Russia is that it has created large compliance costs for taxpayer companies. These costs include the time and money involved to justify claims for VAT credits or refund, the denial of the legitimate claims and the borrowing costs of cash withdrawals by taxpayer companies waiting for refunds.

The Russian VAT is a conventional credit invoice VAT in which a company first pays VAT to its suppliers and then deducts it from its own payments due for the products sold. If the input VAT, paid to suppliers, is greater than output VAT, a company has the right to claim a refund. As a result, many middle sized and large businesses have had the experience of attempting to recover input VAT or a VAT refund.

The substantial part of VAT refund claims come from exporter companies given that exports are free from VAT in Russia, but claims for VAT input credits to be deducted from VAT on sales are also involved.

Last year VAT administration was one of hottest issues in tax policy in Russia. This was reflected, for instance, in the Ernst & Young series of annual surveys of Russian and multinational companies operating in Russia. In 2009, 57% of Ernst & Young respondents pointed out that improvements in the VAT regime (procedures of VAT calculation and refund) were required. Specifically, they criticized the sophisticated rules of VAT calculation, extensive documentary requirements, complicated and lengthy procedures for recovering input VAT, and delays on VAT refunds.

Despite the Tax Code amendments in 2007-2008 which aimed to improve procedures for tax audits and provide clear descriptions of common tax administration procedures, companies have had to spend progressively more on tax issues. According to the survey of Ernst & Young, in 2009 55% of companies had dedicated tax departments, compared to 40% of such respondents in 2008. There is a trend of increasing numbers of employees in dedicated tax departments. In 2009, 31% of companies had 5-10 employees in dedicated tax departments, and 27% of companies had 11-20 employees. In comparison, in 2007 these shares were 24% and 10%, respectively. The main reasons for enlarging these tax departments have been that there are significant differences between statutory accounting and tax accounting; and the documentation requirements are demanding. Taxpayers (especially in large companies) must submit large amounts of documentary support to the tax authorities if they are making a claim either for a VAT input credit, or a refund of taxes on exports. For instance, in 2007 representatives of the tax department of an automotive company complained that they had to use a large truck when submitting supporting documents to the local tax authority office.

Procedures for recovering and refunding VAT, despite changes in the last 2 years made by tax authorities, have become even more problematic for many companies, due to the large amounts of false claims, VAT reimbursement procedures . According to Pepeliaev, Goltsblat & Partners (one of the largest providers of law and consulting services in Russia), last year the most frequent reason for refusals in VAT recovery or refund were faults in supporting documentation, and so-called unfair counterpart suppliers – i.e. suppliers suspected of VAT evasion.

According to tax consultants, refusals for VAT recovery or refunds are often based on minor faults in supporting documentation like an unclear organization stamp or an absence of full address in pro-forma invoices, waybills, acceptance reports, etc. Last years a growing number of input VAT claims were not meet on the grounds that there were tax evaders among the suppliers of a company. Tax consultants reported that in some cases these tax evading companies belong to third and even fifth tier suppliers, i.e. were not directly involved in the business with the company claiming VAT input recovery.

Such problems resulted in a further increase in documentation collected from suppliers, aiming to prove their tax compliance.

The time period for obtaining VAT refunds has shortened, but still remains at 3-4 months and more. According to a survey by Ernst & Young, only 15% of respondents in 2009 received VAT refunds in less than 3 months, 63% of respondents received a refund in 3-4 months, and 15% - in a time period of between 4 months and a year. In comparison, in 2008 the periods for VAT refunds were much longer: 42% got a refund in 3-4 months, and 40% in 4-12 months. This improvement is caused mainly by changing the tax period for VAT (from a month to 3 months for all categories of taxpayers), which automatically decreases the number of claims for the VAT return.

A further key element of taxpayer costs in that a significant part of VAT refunds are only made after court decisions. For instance, the Federal Taxation Service of the Ministry of Finance of Russia reported that in the first half of 2008 the tax authorities declined VAT refunds for a total sum of 78 bln rubles (about $3.3bln). However, in this period the courts approved VAT refunds for a total sum of 30 bln rubles (about $1.3 bln). A survey of Ernst & Young also shows that the majority of respondents recover 90% of their VAT refunds. However, VAT issues remain the most frequent tax issues disputed in the courts. In 2007-2009 VAT cases were almost half the disputed tax cases, and in more than 70% of cases companies were involved in tax disputes with tax authorities.

Not only are VAT reimbursements uncertain in many cases, but companies claiming refunds also bear a risk of extra payments of VAT due and fines. Business associations have reported that some companies have adopted simple risk-averse tax practices: such as not claiming for VAT input credits. This intensifies the problems and increases further the interests costs of cash withdrawals needed for advance tax payments and the lengthy delays for VAT refunds. Such cash withdrawals are substantial for certain sectors. A 2006 study of Russia’s automotive industry showed that VAT payments can constitute up to 50% of the total tax burden of some companies.

In 2007-2008 many taxpayer companies complained of their experience with these administrative pressures. The largest pressure was taxpayers who are involved in all stages of tax dispute – from initial refund claims to the court decisions. In this situation, VAT evaders who do not need to deal with this administrative pressure, receive a competitive advantage over the lawful taxpayers.

Differential Impacts of VAT by sector. One of the most important arguments against the current VAT is that it produces an unequal tax burden across sectors and this impedes economic performance through distortions. The major part of Russian exports of raw materials (with crude oil and gas the largest), and production of raw materials is mostly export-oriented and involves few intermediate products. In contrast, the major portion of higher value-added goods is for the internal market.

Below we illustrate this economic structure using two industries: machinery and equipment (which corresponds to ISIC 382-38416) and crude petroleum and natural gas (ISIC 220) (Table 2). As a rule, companies in machinery and equipment produce higher value added goods than companies extracting crude oil and gas. They also create substantial employment. According to Rosstat data, in 2008 employment in machinery and equipment production in Russia was 4.4 times higher than in crude petroleum and natural gas production. In addition, companies in manufacturing and equipment production usually have higher investment activity than in oil and gas extraction companies. Estimates based on Rosstat data show that in 2008 the capital investment to profit ratio for machinery and equipment was 1.7 times higher than for crude oil and gas.

In contrast to crude petroleum and natural gas, where about 50% of petroleum and 28% of natural gas is exported, more than 80% of produced machinery and equipment goes to the internal market. This inevitably creates a disproportionate VAT burden between these industries.

Table 2. A comparison between the crude petroleum and natural gas and machinery and equipment industries in Russia, 2008

|

Characteristics |

Units |

Crude petroleum and natural gas industry (ISIC 220) |

Machinery and equipment industry (ISIC 382‐384) |

|

Output |

$ bln |

184.7 |

135.4 |

|

Employment |

thousands |

613.3 |

2727.4 |

|

Net financial result (profit less losses) |

$ bln |

28.7 |

2.8 |

|

Fixed capital investment |

$ bln |

38.3 |

6.3 |

|

Employment to output ratio |

Employees / $ 1 bln |

134 |

812 |

|

Investment to net financial result ratio |

% |

133% |

226% |

|

Exports to output ratio |

% |

50% for crude petroleum, 28% for natural gas |

17% |

Source: estimates based on Rosstat and Bank of Russia data

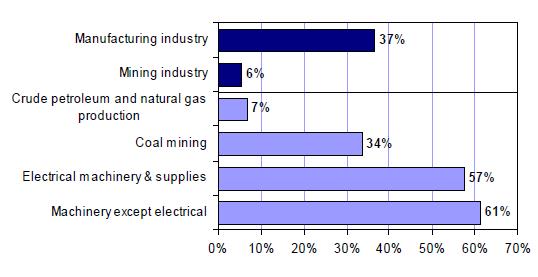

To illustrate the disproportionate industry VAT burdens, we have used the latest available statistics (first half of 2009) provided by the Federal Taxation Service of Russia (Figure 2). We use a comparison with profits to illustrate the relative amounts of cash withdrawals caused by VAT payments with difficulty over VAT inputs credits.

Implicitly this assumes the VAT is borne by the entity paying the tax, i.e. the company, and the tax is not shifted forward to consumers. As such, we focus on effective tax rates relative to profits. For the mining industry in general, in the 1st half of 2009 it needed to withdraw cash equal to about 6% of their profits to pay VAT, whereas for manufacturing industries the relative withdrawal was much higher, reaching 37% on average. However, for the companies manufacturing higher value added goods, this proportion was even greater. For companies producing electrical machinery and equipment, VAT payments are 57% of profits, and for other machinery production – more than 60% of profits. It is worth noting that this inequality in VAT payments was also present in prior years, before the economic crisis. For example, according to the Federal Taxation Service, in 2007 VAT payments by the crude petroleum and natural gas industry were around 20% of profits, and in machinery and equipment – about 55%. The VAT traditionally accounts for the largest share of tax payments by manufacturing industries.

Figure 2. VAT to profit ratio for selected industries in the Russian economy, first half of 2009

Source: Federal Taxation Service of Russia

The higher VAT burden on manufacturing companies requires larger cash withdrawals and result in sharply lower funds for investment. It thus retards development of Russia’s manufacturing sector. In this sense it can be argued, that VAT preserves the commodity specialization of Russian economy and does not promote its diversification into manufacturing.

Problems for producers dealing with small tax exempt suppliers. Another issue with Russian’s current VAT arises with small and medium sized enterprises. The Russian Tax Code provides a VAT exemption for small business units (organizations or individual entrepreneurs) with less than 2 mln rubles (approximately $70 000) revenues over the last 12 months. Small business units with less than 45 mln rubles (about $1.6 mln) annual revenue can also apply for treatment under a simplified taxation system, under which a business unit receives a tax exemption for a number of taxes (including VAT) and pays a single tax on corporate income instead of them. These measures were a part of an earlier tax stimulus package for small businesses. In many cases these VAT exemptions are a discouraging factor for transactions between small tax exempt suppliers and larger taxable companies, since there are no input credits.

This can be illustrated using the example of small tax exempt business units supplying goods to taxable retailers. If a retailer’s supplier is a taxable company, the retailer would pay VAT and recover this VAT at the end of tax period as an input credit. But if a retailer’s supplier is a tax exempt company or individual, the retailer can not recover VAT. In theory, this effect could be easily neutralized if a tax exempt supplier would provide his or her products for the price reduced by the amount of VAT. But, in practice the prices of small suppliers are not cheaper than those of larger suppliers , given differences in production scale, operations management, and other factors. For these reasons, a common practice for retailers (and of many other large companies as well) is to deal preferentially with VAT taxpayers rather than with tax exempt business units.

As a matter of fact, the largest part of small business units (according to national statistical definitions an enterprise with annual revenues less than 400 mln rubles (about $14 mln) and less 100 employees) operate in retail and wholesale trade. According to Rosstat data, the share of small business units operating in retail and wholesale trade was 45% in 2005-2007. In contrast, the share of small businesses operating in manufacturing was 11-12%.

Compliance issues with the VAT for tax authorities

In recent years, the most important VAT issue for tax authorities in Russia has been the rapid growth of claims for VAT refunds, many of which are fraudulent. In 2002 the Federal Customs Service of the Russian Federation admitted that VAT refund claims on false operations were one of the main threats to Russia’s economic security. According to the report of the Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation, in 2002-2006 the amounts of output VAT increased 2.8 times, but the amounts of input VAT increased by 3 fold. The Accounts Chamber also estimated that growth rates of VAT refunds were far ahead of GDP growth. In 2004 nominal GDP increased by 26.5% compared to 2003. At the same time input VAT claims (excluding export refunds) increased to 35.5%, and VAT refund claims on exports – by 45.3%. In 2005 the annual budget losses incurred by false VAT claims were $4.7 bln. The Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting (CMASF) estimated in 2006 that if the VAT refunds continued to grow at the same rate as in 2006, by 2013 refunds would be greater than VAT revenues.

At the same time, the VAT collection rate remained unsatisfactory. Estimates from researchers show that VAT collections were less than 60% of VAT liabilities in 2000s. These estimates are based on average payment and statutory tax rates. The estimates of the Ministry of Finance are higher: 80-90% in 2005-2007 and about 85% in the first half of 2009. However, these estimates differ in that researchers use a comparison between expected VAT revenues and actual revenues. Despite these differences, improving the tax collection rate was set as one of the main tasks for the Ministry of Finance.

Since 2005 the tax authorities have made a number of administrative efforts aimed to improve tax discipline and prevent the growth of false VAT claims. The Federal Taxation Service and the Ministry of Finance suggested a number of directions, including the introduction of special “VAT accounts” for taxpayer companies, with preliminary registration of VAT taxpayers. Such initiatives were discussed but not adopted by the Government.

The more substantial part of tax effort relates to expanding the regulatory authority of the Federal Taxation Service. This includes extensive tax audits and additional checks before approving VAT refunds, imposing additional requirements for supporting documents and taxpayers applying for refunds. According to the media, at that time the Federal Taxation Service recommended its regional and local subsidiaries to increase significantly the number of refusals for VAT refunds. The Federal Taxation Service also carried out an extensive project developing criteria for “unreliable” companies which should be checked more carefully if they applied for a VAT refund. The policy was intended to complicate the process of VAT reimbursement. As a result, as discussed above, the time periods required for obtaining VAT refunds became longer, and the major part of VAT refund claims were fulfilled only after court disputes. The growth rate for VAT refunds was lowered, but the public costs of VAT compliance increased significantly.

Since 2007, a number of amendments to the Tax Code of Russian Federation have been adopted, setting limits for tax audits, terms of VAT refunds, etc. A special procedure for “fast” VAT refunds for large taxpayers (with tax payments exceeding 10 bln rubles (about $360 mln) for the last 3 years) is under development. Nevertheless, VAT administration remains one of the most difficult tax areas and still requires further improvement.

Fundamentally, then, all three of these problem areas – problems in the processing of claims for VAT credits or refunds by business, the interaction of large and small firms, and rising compliance costs for government from fraudulent claims for credits – stem from the multi stage nature of the credit-invoice VAT in an economy with major problems with corrupt practice. The central argument this creates for the sales tax is the easing of these problems by moving to a single stage tax.

The sales tax alternative

To date, the most detailed description and discussion of the sales tax alternative to the VAT in Russia is presented in a report by the Center for Taxation Problem Research (CTPR) This Centre is closely connected to the Finance Academy under the Government of the Russian Federation. The report summarizes the results of a project carried out with the support of the Presidential Executive Office. From the end of 2006 on this report was publicly discussed by the expert community, business associations and government officials. As we noted above, after these discussions the Presidential Executive Office was to develop the idea furthermore. However, to date no other reports on the matter are available, but a Presidential Commission created in 2008 on the issue still exists and is to report.

The sales tax suggested by CTPR is a somewhat unusual variant on a conventional retail sales tax. It is a single stage 10% tax on all final consumption including household consumption, government consumption and exports. Transactions between companies are subject to the sales tax if a transaction was either made in cash or the costs of the transaction do not qualify as production costs. As such the government taxes itself, and both imports and exports are taxed. The idea is to generate as large a base as possible for a single stage tax to have as low a rate as possible, and that all legal entities should be taxpayers, with intermediate sales free from the sales tax through a tax payer qualification scheme The resulting discussion of the CTPR proposal has focused on a variety of potential benefits and risks of VAT substitution by sales tax. The most important of these are summarized below in Table 3.

Table 3. The potential benefits and risks for the Russian economy in substituting the of 18% VAT by a 10% sales tax

|

Potential benefits |

Potential risks |

|

Simplifying tax administration and lowering tax compliance costs |

Budget losses |

|

Less tax evasion |

Collecting taxes at retail level from large numbers of small retailers |

|

Structural effects stimulating diversification |

Complexity in distinguishing between intermediate and final sales |

|

Better tax planning across regions |

Taxation of both exports and imports |

|

|

Additional tax burdens on small business |

Potential benefits of the sales tax proposal

The replacement of VAT by a sales tax in Russia is claimed to be beneficial for business as it would lower tax compliance costs and generate positive structural effects in the economy. In addition, it is argued that substitution of VAT by a 10% sales tax would automatically make the most popular tax evasion schemes less attractive. Also, the revenues from the sales tax can be better planned by regional governments, given population density and other characteristics.

The use of a sales tax instead of the VAT would contribute in a major way to a decrease in tax compliance costs for many companies. As noted above, the VAT is one of the most complicated taxes in Russia, imposing high costs for tax accounting, and requiring the supporting documents and participating in tax disputes if necessary. Compared to VAT, the proposed sales tax is more easily calculated, and given that it does not imply any reimbursements, there is no need for administrative procedures for refunds approval and checking the supporting documents. The removal of multi staging in the tax is thus one of its main advantages over VAT.

The substitution of VAT with a sales tax would also greatly simplify tax administration for tax authorities. This is because the proposed sales tax is simpler than VAT, and the relatively low sales tax rate of 10% will create less incentive for tax evasion. According to independent estimates, in the recent years in Russia the costs of popular tax evasion schemes used for VAT are in the range of 12-13% of the value of sales. Currently, with a 18% VAT, taxpayers finds it pays to use such schemes and bear the risk of legal liability. The consensus view is a 10% tax rate would automatically make such schemes unattractive.

Another important benefit of substitution of VAT by a sales tax is induced structural change in the economy. In contrast to a VAT, which places the manufacturing sector under a much higher tax burden than the export oriented mining sector, the sales tax would offset this and depending on tax shifting assumptions do the opposite. In this sense, the sales tax can be viewed as a stimulus to economic diversification in Russia.

This effect is illustrated in the CTPR report, where 5 types of business units were taken for comparison: oil and gas exporting companies, wholesale trading companies, retail trading companies, companies operating in the B2B sector, and service suppliers for individual customers. Simple estimates provided in the report showed that the sectoral sales tax burden is sharply different than that of VAT because of the elimination of multi staging. If an 18% VAT is substituted with a 10% sales tax, assuming that companies bear the tax on retail sales the effective tax burden on sales for all 5 model companies decreases (Table 4). However, the largest decrease, according to the CTPR calculations, is for the industrial supplier company (B2B supplier) and the wholesale trader company (15 and 11 percentage points, respectively). The tax burden for oil and gas exporters decreases only to 1 percentage point, and for retailers – to 2 percentage points.

Table 4. Estimates of effective tax rates for a 18% VAT and 10% sales tax burden for some typical companies in Russia

|

Companies

|

Estimated effective tax rate |

Decrease in tax burden (percentage points) |

|

|

VAT (18%) |

Sales tax (10%) |

||

|

Oil & gas exporting company |

2% |

1% |

1 |

|

Wholesale trading company |

11% |

0% |

11 |

|

Retail trading company |

12% |

10% |

2 |

|

Supplier to other companies (B2B sector) |

15% |

0% |

15 |

|

Service supplier for individual customers |

16% |

10% |

6 |

Source: Center for Taxation Problem Research

These CTRP estimates thus indicate probable shifts in tax burdens across the various sectors of the Russian economy. However, as there are estimates are only for model companies, they do not provide the complete cross-industry macroeconomic picture of sales tax burdens.

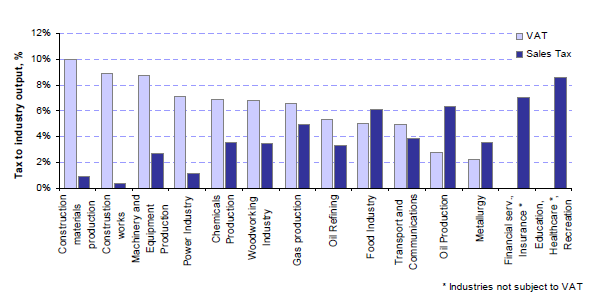

We have also made an attempt to obtain such a picture, aiming to understand more fully the differences in the indirect tax burden in case of a VAT substitution with a sales tax based on the latest available input-output tables for Russian economy (2003 data published in 2006). However, the substantial lag in data presented in input-output tables imposes a number of limitations. First, the latest input-output tables for Russia are based on 2003 data and they use an industry classification which was used in Russia before 2005 and does not comply with the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC). Second, for the comparison between VAT and sales tax we use a 20% statutory VAT rate which was in effect in 2003, and a 5% sales tax which was charged on a limited number of consumer goods. For this reason, our estimates describe the situation as if a 20% VAT was substituted with a 10% sales tax (in addition to the existing sales tax of 5%). This assumption permits us to ignore the low sales tax collection rate in 2003 and the limited range of consumer goods covered by the tax.

Following the sales tax proposed in the CTPR report, we define the sales tax base for each sector of the economy as the sum of domestic final sales to households, government, non-profit organizations, and exports. All data are taken from the input-output tables based on 2003, and we exclude VAT from domestic prices, so as to compare the tax burden distribution of VAT against sales tax. We also assume no out-of-pocket transactions between legal bodies, no tax allowances and no tax evasion. For comparison, we also estimate the cross-industry VAT burdens using the same input-output data. However, these data have limitations. The aggregate data do not permit us to distinguish between large business units and medium businesses, which in case of low turnover could be VAT exempt. This is important especially for such sectors as retail and wholesale trade where a substantial amount of trade is carried out by such businesses. For this reason, we do not make estimates of the VAT burden for these industries having a relatively large proportion of small and medium businesses (like the wholesale and retail trade sector), and for industries which are free or almost free from VAT (financial services, healthcare services). As a result, our comparison covers only about 55% of Russian GDP. We also do not take into account VAT exemptions provided for some final goods and VAT deductions for fixed capital investments. In other words, we take into account only the input VAT deduction (including export rebates) and lower VAT rates for some industries (foods, agriculture, pharmaceuticals, etc). For simplicity, we also do not estimate the indirect tax burden on imports (assuming that the substitution of VAT with sales tax would not produce significant changes in import volume and structure). Finally, we calculate the ratio of estimated VAT or sales tax payments to industry output, to make our tax burden comparisons easier to follow.

The results show substantial differences in sales tax effective rates compared to VAT (Figure 3). The estimates of VAT burden by sector are in line with the observations from macroeconomic statistics – sectors with high value added are exposed to a higher VAT burdens than commodity producing sectors. For instance, most of the VAT burden falls on industries with high value added – production of construction materials (the ratio of VAT to industry output is about 10%), production of machinery and equipment (8.8%), power industry (7.1%). The sectors involved in commodity exports, as expected, experience much lower effective VAT rates (for oil production industry, the ratio of VAT to industry output is 2.8%, and for metallurgy it is 2.2%).

Figure 3. Comparison of VAT and sales tax effective rates across industries in Russia (estimated of using input output data for 2003)

Source: ICSS calculations based on Russian Input-Output Tables, 2003

Estimates of sales tax under the same conditions show a different picture and in general, the results are in line with CTPR results discussed above. The highest effective sales tax rate is for industries and sectors with relatively high shares of final sales in total industry output. Apart from retail and wholesale trade, sectors with high share of final sales are education, healthcare and recreation services (the estimated ratio of sales tax to sector output is 8.6%), financial and insurance services (7.0%), food industry (6.0%).

Unlikely CTPR model company estimates, commodity exporting sectors experience higher indirect tax rates, under of sales tax introduction. The reason is that the export revenues for these sectors are higher than domestic intermediate sales (which are free of sales tax). For some sub-industries, which received the net VAT refunds on exports (i.e. negative values of VAT payments), the introduction of sales tax would also cause on increase in tax rates. A relatively high sales tax rates occurs for oil production (ratio of sales tax to industry output is 6.4%) and gas production (5.0%).

At the same time, for the sectors involved mostly in B2B operations with large intermediate sales, the sales tax burden is estimated to be low (0.9% sales tax to sector output ratio for construction materials production, 1.1% for power industry, 2.7% for machinery and equipment production). Thus, the introduction of sales tax instead of VAT substantially changes the pattern of cross-sector effective indirect tax rates.

Apart from stimulating structural diversification, the sales tax also has the potential advantage of better tax planning across regions. The regional distribution of sales tax revenues are expected to correspond closely with population density. Compared to the VAT, where the regional distribution of tax revenues depends on the spatial location of value chains, it is thus easier to estimate sales tax revenues, optimize inter-budget transfers and maintain budget stability ate a local and regional level.

Potential risks of sales tax

Despite the benefits above, the opponents of sales taxes in Russia point to the potential risks of VAT substitution. The most serious is budget losses because for many companies the tax burden would be lowered. There are also concerns about the definition of final and intermediate sales, which is closely connected to the size of tax base and opportunities of sales tax evasion. In addition, problems of double taxation of exports and small business taxation arise.

Probable budget losses are viewed as the most serious argument against a 10% sales tax. It is worth noting that the issue of budget stability during tax reform was important in Russia even in pre-crisis times when the federal budget had a surplus for almost ten years. According to the CTPR estimates, the introduction of this tax instead of VAT could cause a decline in budget revenues of 2.3% of GDP during the first year (these estimates were made on the basis of 2004 data, assuming that there were no changes in tax collection rates for the various sectors of the economy).

Most of the losses are expected because the structure of taxpayers would be changed. In contrast to VAT, where tax is collected throughout the whole value chain, in case of sales tax the taxpayer is on the final end of the value chain (in most cases – in retail). However, retail trade has low tax discipline. For example, in 2004-2006 it was estimated that VAT collection in retail (excluding the VAT exempts) was 2-3 times below the average VAT collection rate in Russia. Consequently, the introduction of sales tax alternative requires a decision about how to compensate for missing revenues, and how to improve the tax collection rate in the retail sector. According to the CTPR calculations, if the tax collection rate in retail sector is improved to the average values for Russian economy, expected budget losses would fall from 2.3% GDP to 1.2% GDP. Moreover, these losses are to be compensated in the following years by the strong stimulus effect on the industrial sector of the economy. One of the probable solutions for compensating budget revenues suggested by CTPR was to make a step-by-step substitution of the VAT with sales tax over several years. The idea is to decrease VAT rate gradually and simultaneously increase sales tax rates. However, this raises the questions of added tax administration and tax compliance costs, given that there would be two indirect taxes instead of one.

Another potential issue with sales taxes arises with the definition of final and intermediate sales. Currently the proposal is to define the sales tax base as all final sales (i.e. household consumption, government purchases, exports, and purchases paid in cash). However this has to be defined more precisely to prevent tax evasion. The use of registration numbers for purchasers of intermediate products is another option. To date, these definitions are not elaborated yet.

Opponents of sales tax point out to examples of regional sales taxes which existed in Russia in 1998-2003, where the problem of distinguishing between intermediate and final sales was major. For example, as the former sales tax was imposed on sales with cash payments, the popular forms of tax evasion were false non-cash payments and reconfiguration of cash registers. This led to low tax collection rates and eventually repeal of the sales tax. The proposed sales tax is thus unlikely to be as easy to administer in practice as it seems in theory.

In its current form, the proposed sales tax would also create a problem of double taxation of exports. The major part of Russian exports goes to EU, where they are subject to VAT. Since no export rebates are planned with the sales tax, exported Russian goods (including industrial exports) would be less competitive. Estimates made using the 2003 input-output tables show that if exports are excluded from the sales tax base, this would lead to more than a 40% decline in sales tax revenues.

The possible introduction of a sales tax in Russia also raises questions for small and medium size business. To date, about 50% of small and medium size enterprises operate in the retail sector, which potentially is the core taxpayer of sales tax. To date, as discussed above, the small and medium size business units are taking advantage of a special tax regime and are not subject to VAT. If the proposed sales tax were to be imposed on small and medium business units as well, that would certainly increase their tax burdens and decrease their competitiveness. At the same time, if the sales of small and medium size business were exempted from sales tax, tax revenues from the retail sector would fall sharply.

Alternatives to the sales tax

Although not discussed in the debate, there are other options to the continuation of the present credit-invoice VAT. The issue is whether the current problems arise primarily from the multi stage credit-nvoice mechanism used to administer the VAT, or from taxing value added. As long ago emphasized by Shong (1974) there are three different methods of computation which can be used for value added, which lead to three different administrative mechanisms for the VAT. One is the multi staged credit invoice mechanism in current use (and widely used around the world). The two others are the subtraction method of directly taxing the difference between total sales and input costs at firm level, and the addition method of directly taxing wage compensation and capital income (profits plus interest paid) at firm level. With the latter two methods, no multi staging is involved. There are definitional problems with each, and neither has widespread use on which to draw experience but given the collection problems with the sales tax, are alternative options.

To sum up the arguments above in favor of and against the substitution of VAT with a sales tax suggest that compared to the VAT, the sales tax is also advantageous because of its simpler tax administration, which reduces tax compliance and collective costs. The sales tax is also potentially appealing for the development of high value added manufacturing and services. An important advantage of this change is a positive structural effect on the Russian economy, fostering its diversification through the development of manufacturing companies operating in B2B sector. However, the introduction of sales tax would require additional efforts and decisions on political and regulatory level in the field of budget revenues compensation, and neutralization of potential negative effects on exporters and small business sector. Tax collection at retail level also poses a major challenge.

The Global Implications of the Debate and Conclusions

Finally, we note that this debate in Russia on the possible replacement of the value added tax by a sales tax has to be seen relative both to the history of the VAT and its global spread throughout the economies of the world. Since its introduction in France in 1954, the VAT has spread, first as a common harmonization instrument for a tax union in the EU as a common European tax and then through developing countries and World Bank and IMF conditionality, and finally to many other economies around the world including other OECD economies besides the EU such as Canada, New Zealand and others as the goods and services tax (equivalent to VAT). The attractions of the VAT have always been seen as its broad base and its compliance advantages since there is no need to define a retail sale as a final sale since the tax is ultimately paid by those who have no inputs to claim as final users. It has always been advocated also that the tax was attractive because of its self policing properties, namely the issuance of invoices by sellers which have to be matched by invoices claimed by buyers.

However, despite all these advantages, the reality of the VAT in most countries has been more mixed than the claimed advantages in the 1950s. Many European countries such as France had difficulties with bogus companies established to print VAT invoices which disappeared in a matter of days or months. This has been an ongoing problem of tax administration. Equally, bogus or false claims for export refunds have been an issue in many countries. Thus, the administrative advantages claimed for the VAT, in practice have with them administrative difficulties. And also, in practice, the matching of invoices precisely between buyers and sellers does not usually occur because of the volumes of invoices which are involved.

This Russian debate however places the VAT in a different light, when one is dealing with economies in which there are significant difficulties of corruption and compliance. In the Russian case, effectively, the VAT has become close to a cascading turn-over tax because of bogus invoices, fraudulent rebate claims, and the associated difficulties of obtaining refunds. These, in turn, have generated a response at an administrative level which has imposed large compliance costs and documentary burdens on legitimate tax payers. This has reached the point almost where input credits and export refunds are often awarded by courts. As we document above, the net effect has been large increases in the tax burden for manufacturing industries which are engaged in intermediate transactions compared to export resources industries and services. While seemingly an obvious set of difficulties for the VAT, as they have taken to perhaps been taken the extreme in the Russian case. The surprising element is that this set of problems has not centrally entered global debate on the VAT, which continues to be strongly advocated by international agencies such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

The Russian debate therefore is in part a mirror image of the debate which preceded the VAT in many other countries, where the pre-existing taxes were characterized as ineffective and riddled with compliance problems, while the VAT, yet to be introduced, was portrayed as a clean tax, free of many of these difficulties. This was true for instance in the Canadian case with the introduction of the GST, where the preexisting manufacturing sales tax was claimed to have problems of cascading difficulties of definition of final sale, tax exporting through increased input taxes effectively appearing as part of export costs, and other difficulties. The VAT, in turn, was proposed as a way of resolving all of these problems without recognizing other administrative problems to follow.

In the Russian case, the VAT which has operated since 1992 has encountered these difficulties in ways which are perhaps extreme, but they highlight the also major administrative issues involved. It is not that the sales tax is necessarily a preferred option since the tax compliance costs involved in collecting taxes at the retail stage are well known and, in the Russian case, are major, and particularly if large numbers of small retailers operate. An argument made in the 1950s in France was that collecting significant amounts of tax at the early stages of the production process from a small number of large entities was more effective than attempting to collect tax from large numbers of small retail outlets at final stage. Nonetheless, the tax compounding effects which operate against the Russian manufacturing industries emphasize all of these difficulties, and the compliance and collection problems appear to be mounting.

The global implications therefore of this Russian debate seem fairly clear. The VAT is coming under challenge because of its major administrative problems which follow directly from its multi-stage character. These in turn are leading to arguments in favor of the introduction of a sales tax in place of the VAT. To our knowledge, this is the first case where such a debate has taken place in this form, and if it results in the replacement of the VAT in this way, it will be an unnerving precedent for the VAT and its global domination. It is not that the VAT is suddenly going to disappear from the global landscape, but the relative merits of multi-staged and single-staged indirect taxes become less clear and more nuanced.

References

- Collection of VAT: Structural Aspects and Decision Variants (2006) / Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting, Moscow, 2006 (in Russian)

- Concise Estimate of Economic Effects Caused by Reducing the VAT Rate (2008) / Analytical Center “Economax”, 2008 (in Russian)

- Comparison of VAT and Sales Tax (2006) / Center for Taxation Problem Research, Moscow, 2006 (in Russian)

- Ivanova A, M. Keen, and A. Klemn (2005) “The Russian Flat Rate Tax” Economic Policy, vol 20 pages 397-444

- Lockwood B. and M. Keen (2007) “ The Value Added Tax: its causes and consequences” IMF working paper No 07/183

- Keen M. (2007) “VAT Attacks!” IMF working paper No 07/142

- Keen M. and V. Summers (2004) The Modern VAT, IMF

- Key Directions of Tax Policy of the Russian Federation for 2010 and the planned period of 2011-2012. Approved by the Government of Russian Federation on May 25th, 2009

- Kononova V. (2006) Tax Policy for Development of Russian Automotive Industry / Taxes and Taxation, 2006, N 12 (in Russian)

- On Value Added Tax / Law of Russian Federation N 1992-1, 06/12/91 (repealed since 2000) (in Russian)

- Piggott J. R. and J. Whalley (2001) “VAT Base Broadening, self supply, and the informal sector” American Economic Review

- Russia Tax Survey 2009. / Ernst & Young, 2009

- VAT. Value Added Tax”, 2008, #10 (in Russian).

- Shoup C.S. (1974), Public Finance, Halance, Chicago

- Smith S, and M. Keen “VAT and Evasion: What do we know and what can be done?” IMF working paper 07/31

- Emran. S, Stigliz J.E , “On selective Indirect Tax reform in Developing Countries” Journal of Public Economics, 2005 vol 89 pp 2037-2067

- System of Input-Output Tables, Russia, 2003 / Collection of Statistics, Moscow, Rosstat, 2006

- Tax Code of Russian Federation. Part II, Chapter 21 “Value Added Tax” (in Russian)

- Tax Code of Russian Federation. Part II, Chapter 27 “Sales Tax” (repealed since 2004) (in Russian)